In Defense of Bad Movies

In 1995, Paul Verhoeven released a film so critically hated that its lead actress was blacklisted in Hollywood for years. Las Vegas marquees, stripteases, sequined bras, homoerotic rivalries, performing chimps. All these elements somehow find their way into Verhoeven’s trashy, NC-17-rated melodrama Showgirls. Starring Elizabeth Berkley as Nomi Malone, the film follows the aspiring dancer as she rises through the ranks of the Vegas show world. What follows is a chaotic spectacle of sweat, exploitation, and sex. In response, critics engaged in a modern-day tarring and feathering. Some keywords from reviews include: pornographic, misogynistic, shallow, voyeuristic. Each review was like another tomato thrown at the theater screen. When the dust settled, all that remained of Showgirls was a red, pulpy mess.

Nomi’s characterization provoked particular disdain from critics. In her review for The Washington Post, Rita Kempley wrote: “Like the bimbo she plays, Berkley's minimal acting talent limits her choice of roles.” Kempley’s words proved omniscient, as the then-21-year-old Berkeley struggled to book roles or even find auditions at all in the years following the film’s release.

For all intents and purposes, Showgirls is considered a “bad movie.” As a self-proclaimed enjoyer of bad movies, I love it.

So, what makes a “bad movie”? In the context of this article, a “bad movie” refers less to its budget and box office earnings — though critically panned films can be, and often are, financial flops — and more to its critical and cultural reception. The most egregious cinematic train wrecks often have the most bloated budgets. Instead, I am the most interested in critically panned films, films publicly berated, mocked, and ridiculed. I believe such films are worthy of cultural consideration and analysis and are often rich with meaning.

Critically panned movies have always had a life of their own. Since 1975, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, for instance, has transformed from a flop to a cult classic. As contemporary viewers, though, how can we distinguish between an irredeemable flop and a misunderstood masterpiece with today’s critically panned films? I would argue that the line between bad and good is often not so clear. Sometimes, a movie can be both meaningful and bad at the same time.

So Bad It's Good

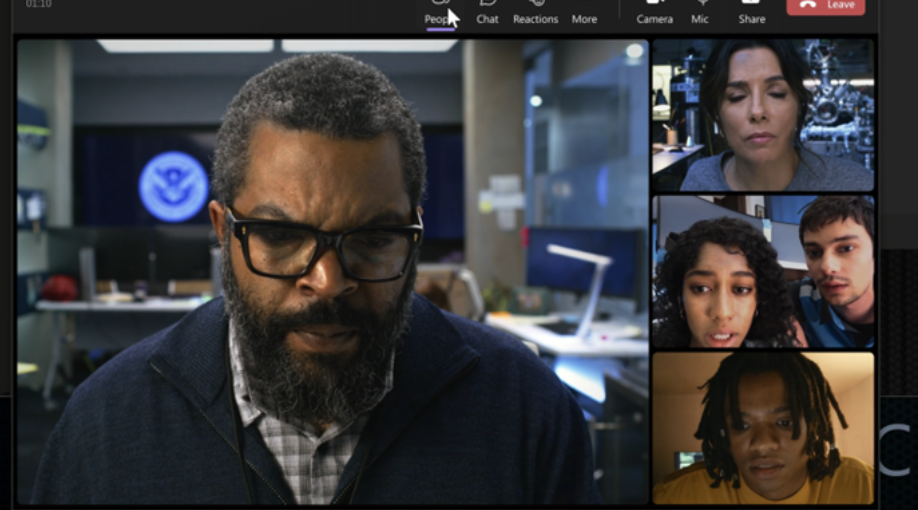

A bad movie can serve as a cultural artifact. Take War of the Worlds, for instance, the 2025 straight-to-Amazon-Prime-Video film based on H.G. Wells’ 1898 novel of the same name. The film follows a U.S. Homeland Security officer played by Ice Cube, as he navigates an alien invasion through computer screens, phone calls, and surveillance cameras. If Orson Welles’ infamous 1938 radio broadcast of the story caused panicked listeners to flee their homes, then the 2025 film caused viewers to flock to TikTok. The online consensus: War of the Worlds is more an Amazon advertisement and humiliation ritual for everyone involved than a coherent movie.

I cannot defend the artistic merits of the film, nor can I defend Ice Cube’s agent. However, I do think the film speaks, in some way, to our current film industry and cultural moment at large. What is War of the Worlds if not a time capsule of the moment in which it was created? Hyper-surveillance, corrupt government officials, constant corporate branding, inescapable screens, data leaks, looming existential threats, that just sounds like an average morning in America. To me, it is only fitting that the 2025 iteration is so corporate, so technological, so hilariously bad. At the very least, a bad movie can make you laugh. And isn’t that valuable in its own right?

Mega-flop or Masterpiece?

In 1973, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather won three Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Circa 2024 and Coppola releases his newest $120 million film, Megalopolis, starring Adam Driver as a genius architect who can stop time. This time, however, Megalopolis is honored at the Golden Raspberry Awards for cinematic failures, which notably nominated Showgirls almost 30 years prior. Since its first ceremony in 1981, the institution has considered films ranging from Cruising, which was protested in 1980 during its release but has since prompted reexamination, to the Twilight movies and Fifty Shades of Grey. As the official awards institution for bad movies, the Razzies serve as an archive of the critically panned and of bad taste. Yet taste formation cannot be divorced from cultural bias. Female actresses, like Berkley, are often judged more harshly than their male counterparts. Erotic, melodramatic, or women-marketed films may also face increased criticism compared to traditionally respected genres.

Just as movies cannot be so easily categorized into binaries of meaningful or worthless, filmmakers themselves are not arbiters of wholly good or bad filmographies. Even Oscar-nominated filmmakers can find themselves winning Worst Director at the Razzies. Alongside a black-and-white photograph of his dashingly handsome face on Instagram, Coppola pleads the case for his misunderstood and self-financed cinematic baby. To him, a film’s impact rests not with its critical reception but with its shifting, lasting cultural relevance. Will Megalopolis stand the test of time, or will it forever be cemented in film history as a “bad movie,” like other Razzie nominees destined for DVD bargain bins at Walmart?

Only Time Will Tell

At Showgirls’ 30th anniversary screening this year, Berkley took to the stage wearing a sparkly top bedazzled with “NOMI” in proud, silver letters. One audience member shouted,“the gays love you!” to which she responded, “I love the gays!” Such is the evolution of Showgirls’ legacy. Since its release, the film has been reanalyzed and embraced as a cult classic, particularly by queer audiences. When Verhoeven set his camera on a half-naked, pole-dancing Berkley, was his intention to create a queer, feminist, camp masterpiece? Maybe, maybe not. But isn’t that the beauty of film? Through film, we can interpret and find meaning in ways both intended and unintended by its creators. Movies are not standalone artifacts. They can morph and accrue new meaning over time, regardless of their critical receptions. Nostalgia is yet another force that can reshape a movie’s reputation over time. While contemporary viewers might long for young Kyle MacLachlan and the film grain of the 90s, rewatchers might feel renewed affection for something they associate with their past.

Many viewers still consider Showgirls to be very, very bad, and rightfully so. I am not arguing that all critically panned films are secret masterpieces that deserve immediate incorporation into the Criterion Collection. If anything, earnest engagement with media criticism and commentary is essential for a media-literate population. I am, however, urging viewers to give these films a fighting chance, to consider them as worthy of serious analysis and reinterpretation before completely dismissing them. And if you watch a “bad movie” with an open mind and hate it anyway, more power to you. One man’s trash is another man’s treasure. But by dismissing a “bad movie” straight away, we run the risk of condemning these movies to a Razzie-adorned jail. Here, the reanalysis process is halted, and a “bad movie” can be classified as such for the rest of its lifetime. In doing so, we lose rich cultural textures that only arise through continued examination of media.

Most importantly, though, cultural reception is not just harmless opinion. It affects the careers and livelihoods of everyone who worked on a film. Critics’ treatment of Berkley verged from plain cruel to overtly misogynistic, halting her career before it even began. Critical reception has the power to shape public opinion, often in ways that perpetually affect not just a movie’s life but the lives of its creators and cast.

Ultimately, no one can govern what a film means to you as an individual viewer. Critics are not a monolith, and neither is cultural reception. As viewers, we can find meaning in the strangest, trashiest places. In any case, I’ll still defend Showgirls on my deathbed, even if no one else will.